Gentlemen’s Guide: Bangkok’s 5 Best Barber Shops

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

[This story first appeared in Koktail Issue 1. All photos courtesy of Gareth Sheehan.]

Polymathic in nature, building surfboards is an intersection of craftsmanship, design, art and science. While no surfing Mecca, Thailand still manages to play host to a number of talented surfboard craftsmen. Meet these three shapers based in southern Thailand who each occupy their own strata in the industry.

Surfboard shaper, iconoclast innovator, and Surfer Mag’s 2007 Shaper of the Year, Australian Bert Burger has arguably evolved the production processes and associated materials of the surfboard building industry more than anyone else in the past 30 years. Traditionalists have typically dominated the board building space, rejecting and marginalising attempts to stray from the standardised norms. In the face of this embedded traditionalism, the then young shaper founded a new era for surfboard construction.

Through experimentation and deep understanding of the physics related to surfboards, he has pushed the boundaries of board performance and durability, inventing the “parabolic rail” and advancing the use of the modern sandwich construction in surfboard manufacture. This led to him co-founding the high-end Firewire brand of surfboards in 2006, the foundation of which is the technology he pioneered that continues to be used at his Sunova factory setup in southern Thailand.

Sunova is located in Khao Lak and not more than 2km from the coastline devastated by the 2004 tsunami. The large warehouse was the former site of a large construction materials outlet servicing rebuilding efforts in the area following the disaster. These days the site services the demands of marine boardsport fanatics around the world. I arrive at Sunova to interview Bert as arranged, but he’s not there—because, well, I’m several hours late. Nevertheless, his son Dylan is present and guides me through the factory, explaining the stages of production and the extensive product line. Like his father, at 25, this kid knows his stuff. One of the first things you notice stepping onto the factory floor is that it is clean, organised and spacious. Although it’s a relatively large factory with 100 workers, it manages to maintain a boutique feel.

Bert on his bike, ready to head out for a beer

Bert arrives as I am finishing the factory tour. A sturdy 6’4” and donning an aloha shirt, dark sunnies, a sun-bleached ponytail and an unfettered Aussie accent, he checks his watch and says, “Usually about this time, I head down the beach for a beer—wanna follow me down?” He mounts a stripped-back Honda moped and I shadow him to a dead-end road a few kilometres from his factory, where a few thatched-roof shanties sit in disrepair next to what looks like a resort abandoned mid-construction. Cold beer in hand, Bert surveys the conditions on the coast and loads me with information about the local waves, describing the mechanics of the swells that originate in the southern Indian Ocean and eventually make landfall on the Khao Lak coastline.

A surfer since he could walk, Bert, now 53, hasn’t surfed in more than a year due to injuries. His torso is still tender from an accident in January 2020 that occurred riding his off-road motorcycle along the same coastline in excess of 100kmph. Suffering a fractured pelvis and broken coccyx from a collision with abandoned fishing gear, he has been dry-docked ever since. His recovery time is compounded by an additional bike accident in which he broke several ribs and cracked his sternum. “I can’t lay on a board or paddle. It’s too painful,” he tells me.

Bert’s laidback demeanour belies the keen business intellect and master craftsman that began his journey shaping surfboards in his hometown of Rockingham in Western Australia more than four decades ago. Growing up a stone’s throw from the beach, he is a third-generation surfer. His Dutch grandfather, who emigrated to Australia in the early 1950s, was an engineer who became a surfer in his forties. Naturally, Bert grew up surfing and by the age of seven was already attempting rudimentary shaping with his own boards.

Bert designs his boards on 3D CAD

Come 1981, at age 13, the year the Thruster arrived on the scene, he repurposed a discarded single fin board by stripping the glass, reshaping the existing foam and reglassing it with an old cotton bed sheet and an $11 tin of resin, adding some homemade plastic fins. Then at 14, he took a two-week internship at Town and Country’s WA factory that resulted in a job offer due to his display of skill and potential. He lied about his age to secure the position—school-leaving age was 15—and began to learn the fundamentals of the trade, doing ding repairs and foiling fins.

Fast forward to 1988 and Bert has his own shaping business. The industry standard PU (polyurethane) boards were the baseline for surfboards at the time—a basic sandwich consisting of a PU foam core, wooden stringer, PE (polyester resin) and a couple of layers of fibreglass cloth. One day, however, while Bert was collecting materials for his factory, a local sailboard maker introduced him to the strong and lightweight materials and processes being used in sailboard construction. Impressed with the weight and strength of what he saw, within a week, Bert had purchased everything needed to build surfboards unlike anyone else. He began experimenting with various foam cores, namely EPS (expanded polystyrene)—a lighter and stronger alternative to PU with the benefits of 3 recyclability.

The recipe for a board with just the right flex, memory retention and durability, however, wasn’t a straightforward task. After a number of boards showed initial promise but ultimately failed to meet the standards that Bert was aiming at, he put it on the back burner until another chance encounter circa 1991 when a balsa salesman walked into his factory. Trialling custom-machined balsa for the top deck of the board, Bert was finally able to create exactly what he was looking for.

As demand for his creations grew exponentially, so did the demand for his time to be spent on non-shaping aspects of the business. For a while, Bert had a two-year waiting list. Re-evaluating his business model, he made the decision to downsize, forgoing middlemen and retailers and selling only to a select customer base at full retail price—at the trade-off of producing only three boards per week. This enabled Bert to return to surfing and distance himself from the frustration of administrative tedium.

He eventually linked up with Nev Hyman of the eponymous Nev boards. After difficulty obtaining funding, Nev recruited Dougall Walker, former pro surfer and former general manager of Billabong, both seeing great potential in Bert’s boards. Then, opportunity came further knocking with the surprise shuttering of Clark Foam, the world’s major supplier of PU foam blanks. Because Bert’s design utilised EPS foam cores rather than PU, they weren’t held hostage by the global blank shortage. Suddenly the embryonic company had close to 100 employees, and production hadn’t even started.

Now enter Thailand. Producing boards in Queensland and California, where initial production was set, simply wasn’t competitive enough to scale. So, in 2007, Bert was sent to the Land of Smiles to set up the Firewire factory, initiate production protocols, train the staff and a directive to spit out 400 boards a week. There were a few problems, though. First, unlike the skilled workers in Australia and the US who mostly have years of experience in the surf industry, the people he was training in Thailand had likely never seen a surfboard, let alone built one. Coupled with cultural differences, he was overwhelmed and called in backup from Oz and America. This created its own issues. New crew members had their own ideas about how the production process should function, ignoring the knowledge Bert had built through years of trial and error.

A perfectionist, Bert struggled to contend with the product direction and management decisions he disagreed with. He parted ways with Firewire and decided to reignite his Sunova brand, which had been lying dormant. He set up shop in Chonburi but after a few years of producing there, made the decision to move his factory to the region of Thailand with the most consistent waves—Khao Lak— taking ninety per cent of his staff with him.

Despite being based in Thailand, Sunova is no cookie-cutter factory pumping out cheap boards to the masses by workers that have never seen the ocean, as is the case with many setups elsewhere in the region. Surfing is a lifestyle industry, and the Sunova ethos upholds that. Bert encourages all his staff to ride something, whether it’s a surfboard, hydrofoil, SUP, kiteboard or tow board— all of which, by the way, are produced and customisable at Sunova.

A variety of products made at Sunova

Unlike the total shutdown of the tourism industry in Khao Lak, even the pandemic was unable to temper Sunova’s growth. Faced with a slowdown in orders at the outset, they added surf skates to their product line. It was a massive success and now accounts for a significant portion of sales.

Today, the state-of-the-art facility is overseen by Bert and his business partners, Martin Jandke and Klaus Christian Mueller—veterans of the industry and both former members of the team at Cobra, the world’s largest board manufacturer. Bert is on daily quality control duties with a sixth sense honed over the decades. “I can hear if someone is using a sander incorrectly from the other side of the factory.” Otherwise, with the factory running like a well-oiled machine, Bert hopes to start experimenting like the old days. He has a new space out the back, isolated from the factory floor, where he brings new designs to life. He is also in the process of completing a studio space where he plans to produce a new video series focused on tinkering and experimentation.

In south Phuket, a grinning, shirtless man in blue Thai fisherman pants dances back and forth along the length of the room to a drum and bass track—the type of jungle beat popularised in the mid-90s by the likes of Goldie (who incidentally lives in Thailand). But I’m not at a rave; I’m in David Sautebin’s shaping bay in Nai Harn.

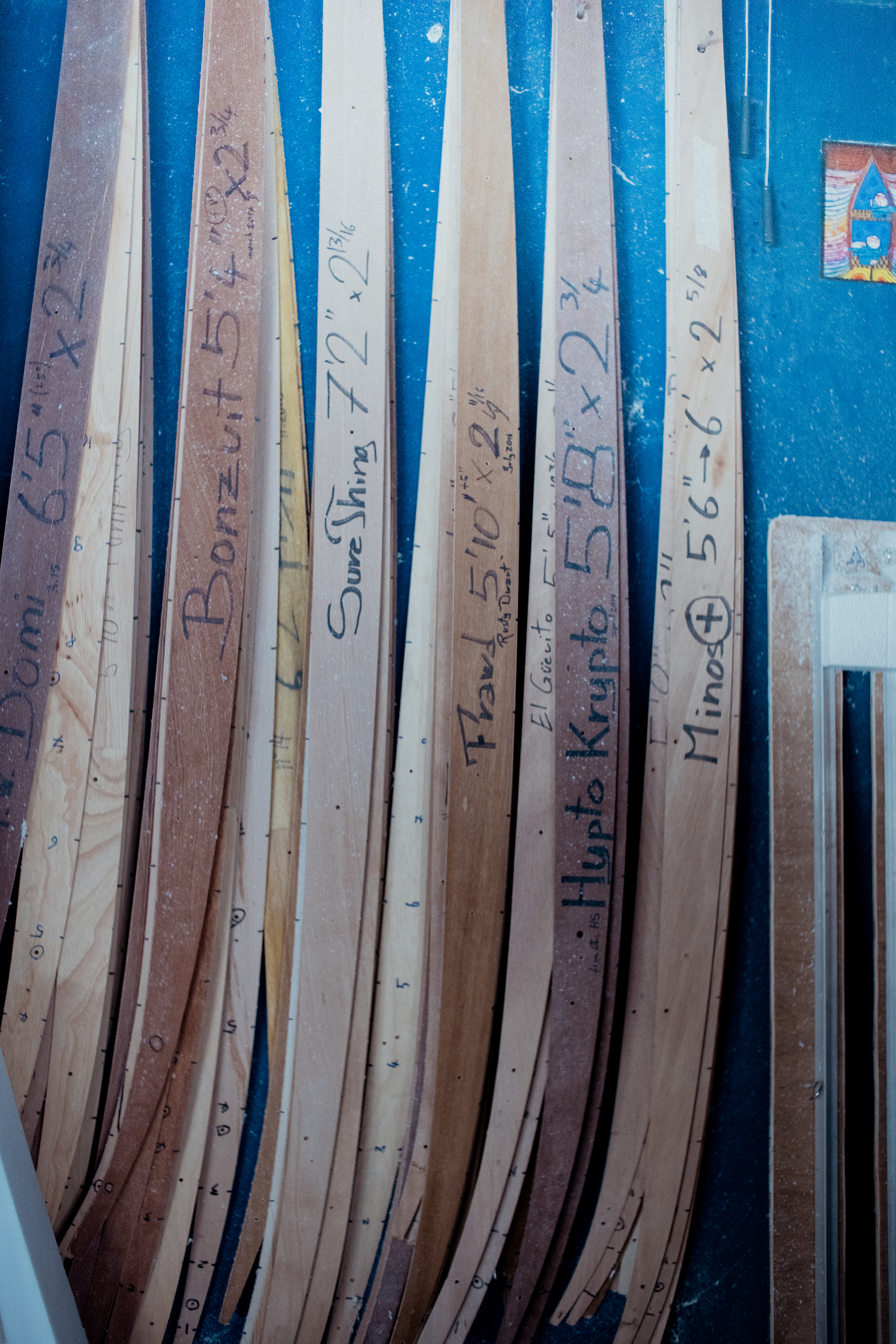

Tucked away at the end of an unpaved road not far from the beach, David’s workshop resembles what you might imagine a shaper’s space to have looked like on Oahu’s North Shore in the 70s. His home is shrouded in palms, banana trees, ginger and overgrown cane grass— the telltale signs of island life. I have a peek around his workshop, which is brimming with materials yet orderly and organised. The diffuse natural light reveals a technical drawing on the bench, a wing for a hydrofoil, one of the ocean crafts he recently began developing for a sector of the board industry that has seen rapid growth in the last couple of years. I then turn to witness the Swiss-native-cum-Thai-resident mechanically reduce a rectangular slab of EPS foam to the familiar curves of a surfboard. The board highlights David’s popular ‘Egginos’ shape and is a custom order for a Phuket local.

Trained as a watchmaker in his landlocked homeland of Switzerland, David first uncovered his obsession with the ocean while holidaying at the French coast as a child. Eventually, he acquired a van and the means to reach the Atlantic ocean and the waves he craved. Suffering from chronic knee pain unresolved by repeat operations, he soon came to discover the analgesic effects that tropical warmth afforded, leading the young surfer to islands in the Caribbean, Japan and Indonesia. He would return to Switzerland between stints to work and finance his impending surfing exploits until 2008, gently persuaded by his peers, he found himself in Phuket following the end of the surfing season in Indonesia. And as happens a series of serendipitous events led to David meeting his now wife, and an extended stay in Thailand.

This path led him to the decision to have a crack at building boards. He canvassed the local hardware stores and suppliers to figure out what was possible. With a loose plan in his head, he set up shop with a budget of US$1,500, initially building an annex off the side of his rented house.

The nascent shaper spent many late nights on the Swaylocks forum—the largest shaping community on the Internet—researching methods, successes, failures and other knowledge within the craft. His quest to source materials locally led to experimentation with various locally available wood veneers for the sandwich construction. One of his earliest iterations featured a bamboo weave that was designed for building purposes, not surfboards. The material was difficult to work with and just not suited to the task. He later discovered paulownia as the ideal timber veneer for his top deck, its benefits including lightweight, strength, resistance to salt water as well as being a fast-growing renewable resource.

David’s board construction is heavily influenced by the method which Bert Burger developed a few decades ago. Indeed, David attributes a significant part of his shaping genesis to Bert. “I wouldn’t have been able to do this without him,” referring to the forthcoming nature with which the Aussie shaper shared his trade methods to the then fresh shaper.

Now an established shaper for more than a decade, David says he is rarely bored. His diverse customer requests give him a large variety of work, each project quite different from the next. All considered, the shaping, laminating, vacuum bagging, sanding, woodworking and so on equate to around 30 individual steps necessary to complete a board. He currently produces around two boards per week and estimates that he is in the workshop for 60 hours or more, though he asserts that it can scarcely be considered work. David revels in the process. The joy he feels from his craft is evident and enviable.

The ethos of David’s Elleciel brand initiated by the acronym LSCL—Live Simply, Consume Less—certainly informs his use of materials. In addition to the extreme durability of the paulownia deck, he incorporates natural weaves like hemp and flax linen as well as specialist basalt weaves (glass fibres produced by heating and extruding volcanic basalt rock). Elleciel also employs the use of “bio resins”, or epoxy specifically formulated to significantly reduce their carbon footprint. Often when laminating with polyurethane, the glasser tends to overcompensate, mixing large amounts of excess resin, which simply ends up as waste that hardens on the floor. David, by comparison, is quite precise with his measurements knowing exactly how much epoxy he will need for each job, ensuring very little is wasted.

He’s quick to express caution when it comes to greenwashing in the industry. “Most of the certifications like ‘gold label blah blah’… it’s all bullshit.” The international brand of bio resin, which David uses exclusively, is produced domestically in Thailand. Although the product does go to considerable lengths to reduce its carbon footprint—up to 50 per cent compared to standard epoxies—the formula itself, he tells me, is at most a third bio-derived. He reminds me that the most environmentally-friendly board is the board with the longest lifespan. To give credence to statements like this, it is definitely true that the average PU shortboard is more or less a disposable product. Seldom do these boards make it through an entire season anywhere that features consistent overhead surf. David’s boards (and indeed Bert’s) are light and very impact resistant by comparison and have a lifespan that can typically be measured in years rather than months.

Customers are encouraged to touch the boards at David’s shop

Beyond custom orders, the price of which begins at 18,000 baht, David stocks a range of boards and surf accessories at his Green Room store in Rawai. Departing from the standard “do not touch” signs one invariably finds on a rack of PU boards, customers at David’s store are encouraged to touch the boards on display. Elleciel’s popularity has David’s order capacity spoken for several months in advance and you can find his creations appearing in a number of surf shops internationally. Still a dedicated slave to the wave and with the benefit of being his own boss, David can be found surfing or kite-foiling around Nai Harn virtually every day.

Adisak Atipongtawon is the archetype of a backyard shaper. Born and raised in Phuket, Adisak, who goes by Joe, is a graphic designer by trade who surfs and shapes boards in his free time. For the past five years, he has produced on average six boards per year under the brand Joe Craft. His clientele primarily consisting of friends, Joe’s operation is by no means a commercial enterprise, though he does have one repeat customer from Japan.

Residing in Phuket Town, Joe’s shaping bay is modest. The carport adjoining his townhouse shared with his two beagles Kai Toon and Jija, doubles as his board-building hub. It’s compact but efficient. A PVC roll-down panel acts as a door. A handful of boards are on racks above the main setup, and T8 lighting tubes are in their obvious position. A minimalist, Joe leaves no superfluous tools in sight.

I first discovered Joe via an Instagram hashtag, which led me to an image of one of his boards. It looked impressive—the work of someone who has taken the time to consider what they are doing. Clearly driven by a love for classic Californian and Australian surf culture, his boards feature glossed out topcoats, pastel tints and retro board outlines. Joe cites the likes of Bob Mctavish, Tyler Warren and Ryan Lovelace as key figures influencing his style.

So how did this 36-year-old hobbyist get to where he is today? The IT graduate shaped his first board around five years ago, though it was not until after several years of online research that he finally tried his hand at the craft.

Joe also builds his boards with an EPS blank and epoxy resin, as well as the addition of a polyurethane finishing coat, which allows him to buff the board to a glass-like gloss. He has no preference in materials and simply builds boards using this method because the materials are readily available. He believes all materials have their advantages and entertains building PU boards in the future.

He tells me the Thai surf scene has started to mature in the past 3-4 years, observing the emergence of a number of talented, local surfers. He predicts it will help drive a healthy future for surfing in Thailand. With his day job gobbling up six days of the week, the Phuket local hopes to have his own small board shop in the future… as well as more time to surf.

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Pets, as cherished members of our families, deserve rights and protections that ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

What happens when Bangkok’s dining scene expands beyond the familiar. Ethnic border ...

The dark elegance of Frankenstein’s costume design reveals itself. Gothic and romantic ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy