Koktail Konversations Ep. 6: Toby Lu on River City Bangkok’s Next Chapter

Toby Lu reflects on River City Bangkok’s evolution and how art experiences ...

VERY THAI: In this regular column, author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture and topics related to his best-selling books ‘Very Thai’ and ‘Very Bangkok.’ As the 4th Thailand Biennale opens in Phuket, this column explores its thrilling art, and what its challenges say about Phuket and the biennale’s future.

Few places have kept changing so utterly as Phuket, which is entering yet another phase. After a millennium as an Indian Ocean port, then settlement by immigrant Chinese, it got pulled apart for a century through the extractive industries of planting rubber and mining tin. Four decades ago, Phuket totally flipped to mining tourists. Now Phuket embarks on mining art for soft power by hosting the 4th Thailand Biennale. Here are my own extracts.

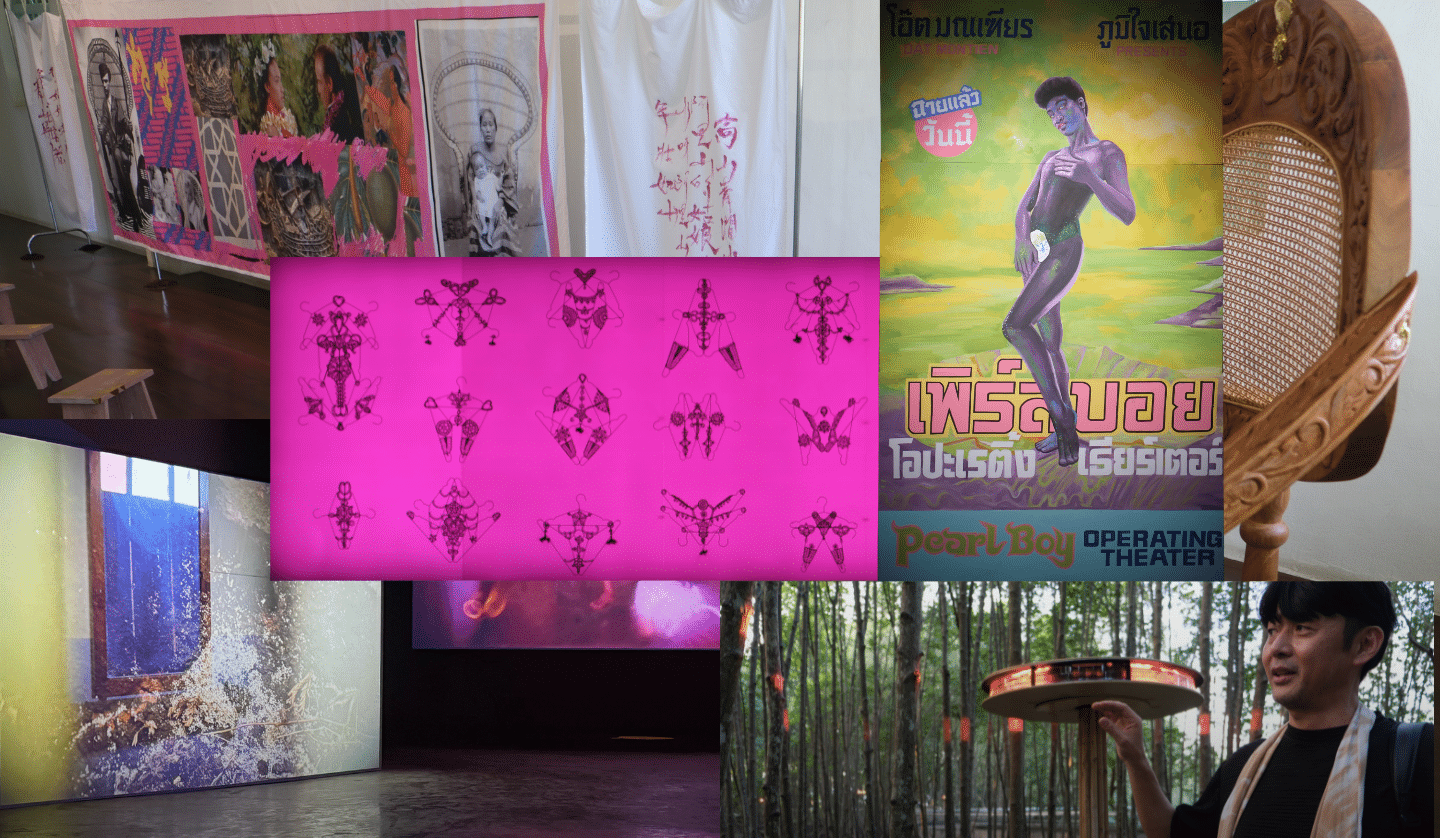

Phuket and the Culture Ministry are adorning the ‘Pearl of the Orient’ with some magnificent art for the peak season until 30 April 2026. The Biennale reveals compelling contrasts to Phuket’s holiday cliches, with deep and often surprising installations. It’s now all open, but launching it incomplete on November 29 has raised questions about the whole venture. Across the island, sea breezes flutter banners bearing the theme ‘Eternal/Kalpa,’ a reference to the Hindu-Buddhist measure of cosmic eons – a long way of saying it’s about ‘time.’

Time is confronting in a culture that lives in the moment and erases awkward histories. The curators pointedly dwelt on relics of Phuket’s past. Arin Rungjang is known for reinterpreting narratives, and his co-Artistic Director, Sino-Australian academic David Teh, wrote Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary. The other curators are Marisa Phandharakrayjadej and Hong Kong’s Hera Chan. Many of the 62 artists or collectives (Thai unless noted) have wrought stunning work about the island’s marginal groups, exploited ecology and hidden stories.

In the absence of an art museum to anchor a core exhibition, their works spread across 19 venues, plus 13 independent ‘sala’ pavilions. Three free shuttle bus routes serve the sites, with Phuket Town as the hub. Almost all the art was commissioned for this Biennale, so it matches the spaces well. Many installations are affecting and stay long in the mind.

Some art fills ornate rooms of Peranakan houses whose restoration has driven Phuket Town’s resurgence. Most recolonise abandoned buildings, which adds character and an ‘urban adventure’ frisson. Other spaces include a stadium, the waterfront Saphan Hin park and Anuwat Apmukmongkhon’s mobile BangLee Pink Karee Puff vendor cart. His roving is live-streamed to a pink room of crowned nudes in the old Thai Airways office.

In a pretty Peranakan home, batiks with rebellious motifs billow beside a warped peacock chair and artefacts from Nathalie Muchamad’s Javanese-Kanak roots. These genteel ‘sceneographies’ mask the indentured labour behind colonial era artefacts. Built by a Hokkien tin magnate Tan Lim Yon, the house stands oddly beside a life-size mural of itself in the old Kathu Liquor Distillery Excise Department.

There, Wu Chi-Yu relates camphor extraction in his native Taiwan for the celluloid industry, except he conjures his faux-vintage films and photos using AI, forcing us to question all ‘evidence.’ Just as surreally, Indonesian Riar Rizaldi critiques beliefs and science in a film about how minerals were found by tracking plants eaten by the near-extinct, Javanese rhino, which haunts the museums we build to what we destroy.

The Asian economic destruction of 1997 began in the Bangkok Bank of Commerce. In its gutted Phuket branch, Bougainville artist Taloi Havini hangs spirals of a simpler currency: Pacific shells. More shells encrust tyres that sensors rotate amid stormy lighting and maritime sounds in Rungruang Sittirerk’s ode to the tenuous survival of Phuket’s remaining Urak Lawoi sea gypsies. Up top, the 1970s origin of hi-so lifestyle flares in Ariane Sutthavong’s archive of Suwanni Sukhontha, a Thai novellist whose pioneering indie magazine Lalanabridged art, fashion and social commentary.

The Yi Teng Market never opened due to land disputes, but its graffitied hulk remains. On the fish counters, Pratchaya Pinthong splays 300 photos by Sirachai Arunrugstichai of environmental and political struggles. Upstairs, Pratchya invited swiftlets to colonise its rotting recesses as an ongoing legacy. This grim site resounds to sensor-tripped birdsong and sounds that help regenerate coral.

Nearby, the Poon Phol Building was a failed store, but makes a fine gallery, with six fan-shaped floors. Standouts are a film of Isaan village villas by Taiwanese auteur Tsai Ming Liang and three captivating animations by Haig Aivazian of Lebanon. Italian Rosella Biscotti turns batiks into cast rubber to retell stories of women and Austrian Olivier Laric’s bronze gecko evolves into furniture. Serbian Aleksandra Domanovic lists cities by temperature on a flight departure board that blandly records abnormal shocks in climatic time.

Pearl Theatre and Pearl Bowl were built by a tin mining family as the acme of boom-era adult amusement. Now vacant, the cinema retains tromp l’oeil murals from its stint as a novelty hall amid saturated lighting in what’s the standout venue. Its halls converge on a black garden and reflecting pond by the Indonesian performance artist Melati Suryodomo. Featuring cones where you’re invited to speak your mind, this eerie invocation to accept life’s dark side is bathed in purple light and electronica by Singaporean Yuen Chee Wai.

The dark side continues with a provocative array of bikini-like figures, Thai hair artist Imhatai Suwattanasilp laced coat-hangers using filaments from the wigs of trans cabaret performers. Probing further in ‘Pearl Boy,’ Oat Montien parallels the process of pearl farming with the life of male sex workers in Patong. In shower-show cubicles, oysters hang in shibari knots before the shellfish get painfully seeded in their gonads, leaving a pile of neon-bathed nacre topped by a pearl necklace.

‘Pearl Boy’ by Oat Montien

Pearl’s tomb-like exit hall was turned by Thai-Japanese videographer Taiki Sakpisit into a mesmerising mausoleum to the 1879 Kathu massacre. Black lanterns flicker and the immersive soundtrack swirls to multiple projections. You have to keep glancing over your shoulder as secret society feuds cause the murder of 400 tin miners, whose ghosts refuse to be silenced. It leaves you feeling chills. Don’t ask if any of the sites are really haunted…

The vast Pearl Bowl, gutted of its ten-pin alleys, opens with fisherman Doloh Chetae mapping human disruptions of Pattani Bay. Inside, five giant screens show the impact of snorkellers and motors on reef and mangrove idylls, filmed by Alex Monteith, Maree Sheehan and Apiwat Thongyoun (from Belfast, New Zealand and Phuket). They borrow the crashing soundtrack emanating from animations by France’s Noémie Goudal of ecology collapsing. It’s a transfixing Biennale spectacle.

Thai biennales tend to salute dead masters and leave landmarks. Literally the most spotlit art is a piano retrieved from the Tohoku Tsunami by the late Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto. Dominating the 4000-Seat Stadium, it plays notes from within a reflecting pool, ringed by paintings evoking the 2004 Tsunami that traumatised Phuket. In a side room, architects Chatpong Chuenrudeemol and Phuket’s Eakapob Huangtanaphan charmingly modify the Urak Luwoi’s impromptu transit – a sidecar and moveable boat shelter – embodying their forced shift from sea nomads to precarious settlement.

Archives of Minnette de Silva’s 1950s innovative Sri Lankan housing share the modernist Phuket Contemporary Art Gallery with models for a children’s library by Ryue Nishizawa of Japan to be built at Nai Harn bay. Installed at nearby Cape Promthep, a moon dial by South African Nolan Oswald Denis will later track lunar time permanently at Surin beach.

In other outdoor art, Pitupong Chaowakul’s climbable red maze cube will be a long-term attraction in Saphan Hin Park. Along the adjacent mangrove walkway, everyone swoons at the sublime lighting by Bangkok-based Japanese Eiji Sumi. Using colours that encourage tree and fish growth, he evokes the spiritual protection of tree ordination. Atop Khao Rang viewpoint, tattered jute sacks imbued with manual labour have been swathed around the gazebo by Ghanaian Ibrahim Mahama, who’s No 1 in Art Review’s ‘Power 100’ of world art figures.

Eternal/Kalpa launched on November 29, with a folksy parade of handmade floats and aunties dancing in Southern kebaya blouses. Unfortunately, the biennale was only 70% done, though it was all complete by December 13, so media didn’t get to see work at Chao Fah Power Station and two shrines. The unready venues, unresponsive systems and late payment were widely attributed to the bureaucratic seniority culture. Oat Montien, hosting the afterparty in drag, lampooned those flaws to cathartic cheers.

Structural problems really matter. State projects are paid in arrears – usual for firms, but not for distressed artists having to pay in advance. As the excellent Biennale guide book arrived late, the ‘press kit’ bag was empty except for a yellow flag to wave at the launch as if journalists are cheerleaders! The state now funds the arts well, but soft power only comes from how other people feel.

The curators wish the Biennale had its own institute like, say, TCDC.

“The commitment is there, the budget is enough, but if they don’t make an arm’s length organisation, it’s doomed,”

they told reporters.

“The inappropriate structure has a cost that isn’t felt by the organiser, but was very exacting on the participants – and it shouldn’t be. The artists had to operate on trust [and] on their own funds for far too long. If you have a body that can make decisions in the interests of the platform, the future is very big.”

Biennials are by definition every two years, but normally in one place. Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB) was the private initiative of Apinan Poshyananda and corporate sponsor Thai Bev. The state responded by making its own rival biennale the same year, in Krabi. The Covid hiatus enabled a wiser reset to alternating with BAB, as at Khorat and Chiang Rai. But that means Thailand dilutes the impact with annual biennials!

Decentralising projects is laudable, but takes the Biennale to ever-less-equipped provinces. The curators have to train-up localities that lack culture management experience, suitable venues, or fluency with contemporary art.

Chiang Rai worked well as it had a new art museum, star curators who were also locals, many resident artists and officials attuned to the art economy. Picking Phuket despite the lack of art infrastructure meant that large spaces were mainly empty buildings that needed fixing. Yet re-purposing old structures is a valiant sustainable cause that needs role models. If Phuket wants an art museum, they could easily convert Poon Phol, which has imposing presence, great spaces and views of hills.

Some insiders reckon the Thailand Biennale should alternate between Chiang Rai and another regular city, or give itself more time as a trienniale. Yet it will next reincarnate in 2027 in Rayong. A surprising choice to many, rich Rayong nevertheless has migrant cultures, eco issues and industrial edge, with plenty of warehouse spaces. But they’ll have to squeeze a kalpa-long learning curve into two short years.

This periodic column, Very Thai, is syndicated by River Books, publisher of Philip Cornwel-Smith’s bestselling books Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture and Very Bangkok: In the City of the Senses.

The views expressed by the author of this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Koktail magazine.

Toby Lu reflects on River City Bangkok’s evolution and how art experiences ...

VERY THAI: In this periodic column, author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Once considered traditional, the sbai is now driving a new wave of ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy