Freen Sarocha’s Airport Look Sets the Tone for Valentino Couture 2026

Carefree and elegant, the 27-year-old actress stuns fans with her new casual ...

VERY THAI: In this regular column, author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture and topics related to his best-selling books Very Thai and Very Bangkok. As Thailand passes a new law protecting ethnic minorities, this column, he explores the Princess Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, which records and promotes ethnic cultures at a time of risk and hope.

Thailand has always been a multi-ethnic place, yet for the first time a new law puts that fact in writing. The Act on the Protection and Promotion of the Way of Life of Ethnic Groups will go into effect soon, when published in the Royal Gazette. Remarkably, Parliament passed the bill with huge majorities, after decades as a contentious issue that had seemed insoluble. That this liberal measure passed during a border conflict – with ethnic insults drenching social media – is even more astounding.

The bill resulted from years of effort from communities, civil society and state agencies. It covered so many departments – interior to defence, education to welfare, culture to commerce – that it was hard to coordinate. National-minded officials weren’t focused on minorities – and were arguably a source of problems the bill sought to solve. So this thorny knot landed on the desk of the Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre (SAC).

This public organisation, under the Ministry of Culture since 2000, had been quietly accumulating expertise in local cultures since its founding in 1994 by Silpakorn University. The SAC researches from local people directly, funds scholars and works with universities on ethnic studies –– a popular cause of this era.

The SAC hadn’t been engaged politically, but its earnest diligence was ideal for defusing tensions. They networked with communities, provided essential data, and helped initiate a draft along with the Indigenous Peoples Council of Thailand, Move Forward Party, the parliamentary committee, and the community rights network P-Move (the People’s Movement for a Just Society).

What got the bill through the conservative senate were crucial word changes: “indigenous,” used throughout drafting, became “ethnic,” while “groups of people” was specified as “groups of Thais.” Those tweaks enable the fair and equal treatment of minorities to go ahead, while skirting awkward questions of legitimacy, allegiance or who counts as native. Guardians of state unity couldn’t countenance restive Malays in the Deep South being recognised as indigenous. Besides, “ethnic” is more inclusive. It also embraces peoples who settled here after the Tai tribes, notably Chinese, Lao, Shan, Karen and Hill Tribes.

Categorising all minorities as subcultures under “Thai” is a less strict version of an old rule. Since 1905, the census has not allowed “Lao” as an ethnicity, so that 40% of the population had to put “Thai.” Among the 12 Cultural Mandates imposed by the dictator Phibun Songkhram in 1939-42 are strictures that all citizens are “Thai” and couldn’t even divide that by, say, Northern or Southern Thai.

Minority rights vex some nationalists. Cultural Mandates still inform official statements, but that nation-building effort has mellowed to allow regional pride, albeit under possessive labels like Thai-Isaan or Lanna-Thai. A major reason for codifying official Thainess was to acculturate millions of Chinese sojourners. Once that was achieved by the 1990s, Chinese and other ethnicities gained confidence to express secondary identities under Thainess. This Act doesn’t seek disunity, but rather brings marginalised ethnic groups under that umbrella of acceptance.

Over the decades, imposition of Central Thai norms and the neglect of minorities has put Thailand’s cultural diversity at risk. Coverage of ethnic ways invariably describes them as “fading,” “threatened” or “disappearing.” Many changes contribute to that erosion, not least TV, social media and modern consumerism. When teens can become TikTok hosts, who wants to carve teak, sew costumes or apprentice to a master of puppetry?

Thailand had been slow to value and document cultures at risk. Then the 1997 economic crash forced a reliance on indigenous resources. A revival in phum panya (local wisdom) sparked the Thai design and spa industries, infused fashion and spurred initiatives like OTOP to market village crafts for contemporary use.

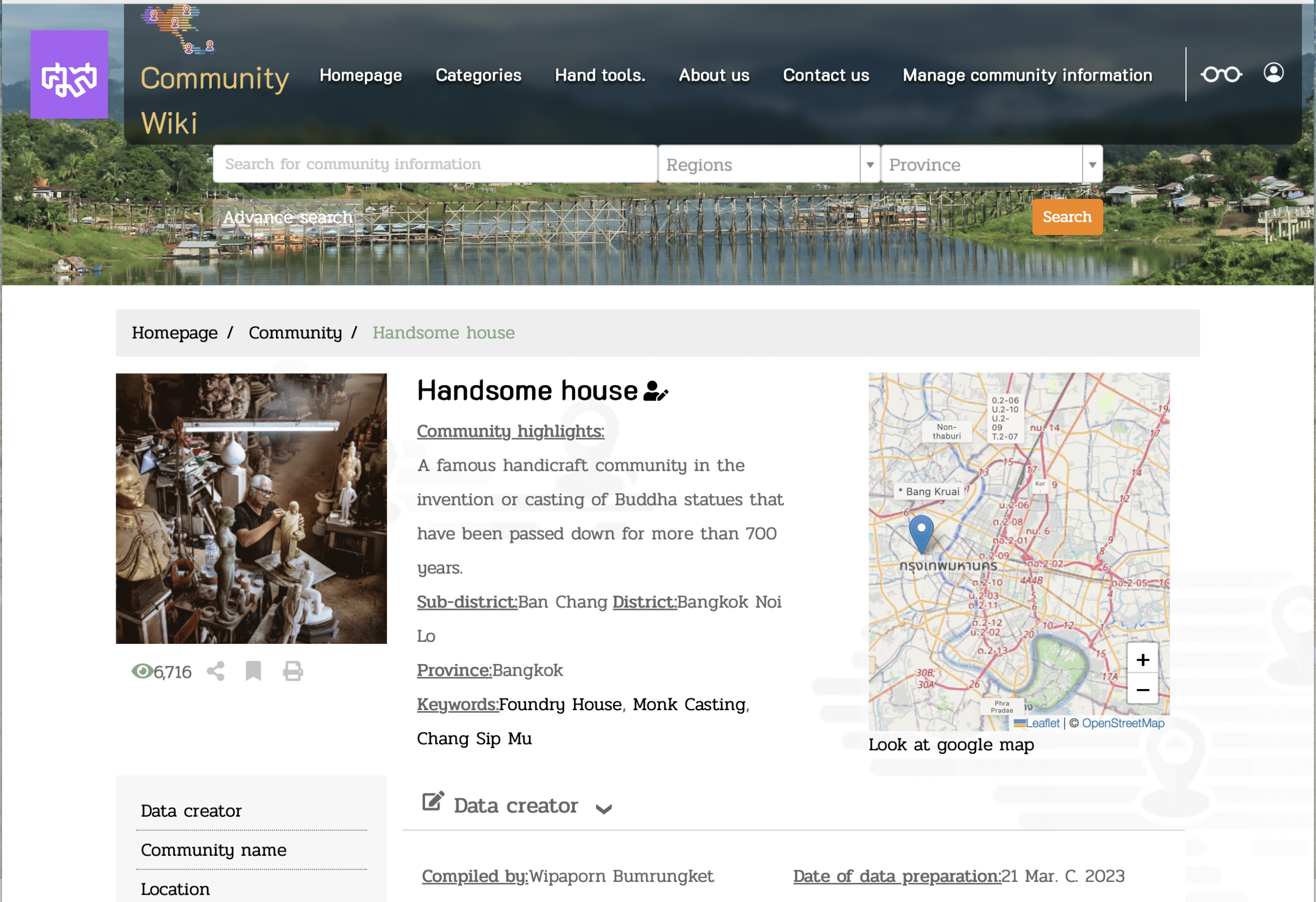

It became urgent to record the lore that was dying with its last practitioners. TCDC (Thailand Creative & Design Centre) has done some oral history. Most extensively, SAC has been compiling a database of ethnic community traditions, WikiChumchon (WikiCommunity (https://wikicommunity.sac.or.th). It is open to all, and automatically translatable. The headings are based on the “7 Tools” that anthropologists use with locals to discover their kinship charts, life stories, history, calendar, organisation and cultural capital.

“Many communities have a person or group who work on this,”

notes Suniti Chuthamas, an SAC anthropologist I first met on a community tour.

“We also give funding to locals to collect their own stories, data, objects and other things. Our teams go to help them, but some work with a local university. Professors send students to help with the fieldwork.”

What the villagers upload then gets checked by scholars and edited to ensure accuracy. As a way to stimulate oral history, SAC gets residents to hand-draw maps. The map for Baan Khongkha on the Mae Khlong River reveals insider details like the shrines, boat noodle shop and landmark tree species. As Suniti says:

“Some of the entries are very rich. We have become a reference for the whole country.”

The Act aims to protect and promote, which seems ambitious, but the process of research can spark initiatives. Some communities didn’t realise what they have is special – or couldn’t express it in relatable ways.

“At Masjid Bang Or in Charansanitwong, the elders and the younger generation cannot talk to each other very well,”

Suniti explained.

“The community wrote that their food is simple, but our researchers noticed they have a really unique cuisine. So we used cooking as a way to connect elders and the young, through teaching the recipe for their tomato biriyani. Their own food and culture then become valuable in their community.”

Once value becomes apparent, momentum can build naturally, as Suniti elaborates.

”Masyid Bang Or formed an alliance with Buddhist temples around there like Wat Arwut. Every month they present their own cultures to the public in a festival. People from around Taling Chan and Bang Phlad go there for food and cultural talks. Auntie Urai Mohammad is the one who demonstrates how to cook rhum, a net pancake made from egg stuffed with shrimp, coconut and cilantro. This delicate snack was mentioned by King Rama II. It’s starting to disappear, but this community keep it strong, and they’re are famous for it now!”

In WikiChumchon you can find the sites by searching their kind, whether rural, urban, suburban, moo baan estates, downtown (like the Prachanaruemit woodworker street) or community networks. Or you can also browse a zoomable map marking all 2299 sites. If you’re travelling somewhere, look in WikiChumchon for added depth on the area.

Anyone can visit SAC’s building itself, which is a short ride from the MRT. They hold workshops, seminars and an anthropology conference every July. Year-round they host permanent and temporary exhibitions in the building and café. The current show, ‘Sail the Seven Seas,’ about Southeast Asia from 9th to 14th century Arab-Persian Accounts, was based on Suniti’s book.

The extensive library has antique palm-leaf manuscripts and epigraphy of ancient inscriptions, which are all digitised. Some collectors and researchers donate their invaluable materials. SAC also do joint projects with École française d’Extrême-Orient, which has an office there.

Under the previous director, Dr. Komatra Chuengsatiansup, the SAC gained a higher profile with more user-friendly engagement. The new director, Asst. Prof. Prae Sirisakdamkerng, hailing from Silpakorn, has been active in peace-making in the Deep South. She is an advocate of ‘cultural fluency’ – the ability to navigate multiple cultures with sensitivity and acceptance. For the Act to succeed, Thailand will surely need to be more culturally fluent. As those ethnic sub cultures get recorded and legally recognised, next comes the really hard job: preserving those traditions and nurturing their potential.

Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre

20 Borommaratchachonnani Road, Taling Chan, Bangkok 10170

02-880 9332, www.sac.or.th,

Monday-Friday 8am-17pm

This twice-monthly column, Very Thai, is syndicated by River Books, publisher of Philip Cornwel-Smith’s bestselling books Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture and Very Bangkok: In the City of the Senses.

The views expressed by the author of this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Koktail magazine.

Carefree and elegant, the 27-year-old actress stuns fans with her new casual ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Thai superstars attended Milan and Paris Fashion Week 2026, marking a strong ...

Looking for something to be inspired by? Here is your guide to ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy