Get to Know Yaya Through the Stories of Flavours and Norwegian Seafood

Join Urassaya “Yaya” Sperbund in her kitchen where family, culture, and Norwegian ...

VERY THAI: In this periodic column, author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture and topics related to his best-selling books Very Thai and Very Bangkok. Here, radical new ways of presenting Khon masked dance highlight challenges in how best to preserve Thai traditions.

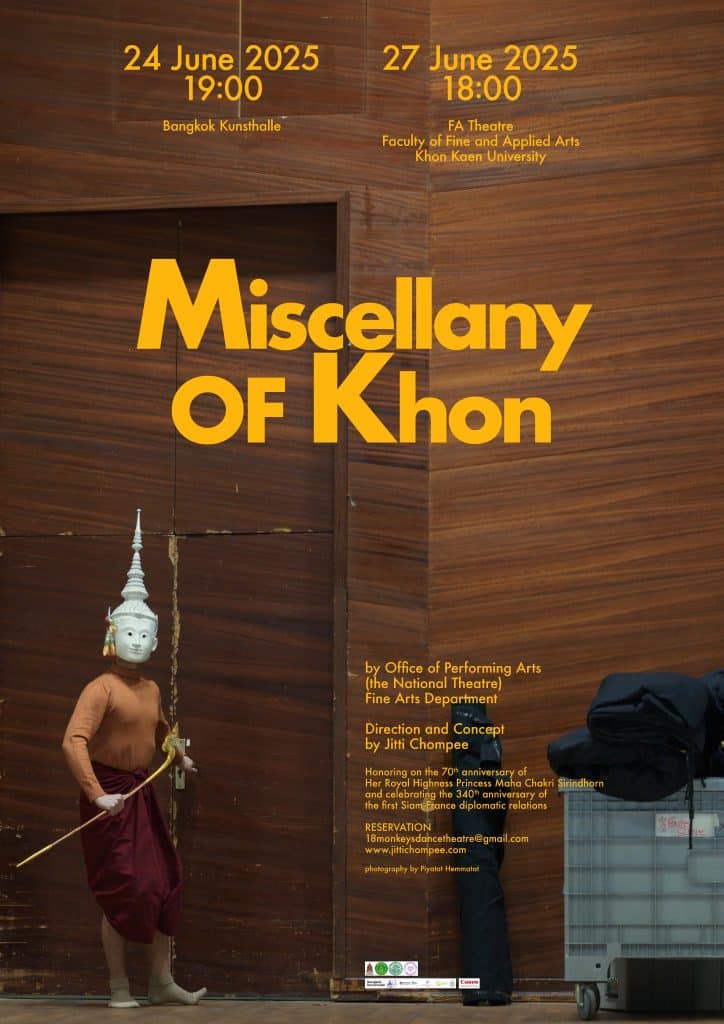

That was the dilemma mulled by Thanpuying Sirikitiya Jensen over long conversations during Covid lockdowns with her friend the contemporary choreographer Jitti Chompee. Gradually, they developed a collaboration to make this formal art more accessible. The resulting documentary film and two contemporary Khon performances recently had their Thai premieres, and they discussed the project on stage at the Alliance Française. Future screenings await a distribution deal, but the dances have further shows on August 16-17 in Khao Yai.

Meanwhile, Jitti is launching an initiative to found a National Centre for Choreography with the country’s most globally renowned dancer, Phichet Klunchun, who also just held the Thai premiere of a Khon-related duet, ‘Number 60’. Suddenly, Thai dance is having a rare moment in the spotlight.

Khon is the earliest example of Thai soft power. The Khon troupe of Nai Butr Mahin visited Paris in 1900 and inspired the star of the Ballets Russes, Nijinsky, to create the ‘Danse Siamoise,’ a pioneer piece of Modern dance. Pichet critiqued that hybrid ballet in his 2010 show ‘Nijinski Siam’. A century ago, Khon was a hip exotic export, but instead of continuing to innovate like ballet, bhangra or kabuki, Khon calcified with bureaucratic inertia.

To traditionalists, Khon is sacrosanct. For centuries, Asia’s Indianised kingdoms justified their rule through India’s righteous epic The Ramayana. Khon dramatises Siam’s version, The Ramakien. Its ritual performance at court animates the legitimacy of state power. Still today, the epic resonates through Thai culture architecture, design and moral stereotypes, like the characters in lakhon soap operas.

As Khon is a sacred offering and an icon of official Thainess, the Fine Arts Department (FAD) guarded its integrity. Khon highlights play daily for tourists at the Sala Chalermkrung Royal Theatre, while sumptuous productions are staged annually at the Thailand Cultural Centre. The staging has developed, with lights, lasers, dry ice, elaborate sets, and devas floating on wires. Yet modernisation wasn’t allowed for the story, characters, symbolism, nor even the costume.

Thanpuying Sirikityiya – daughter of Princess Ubolrat – is a historian with the FAD. Her involvement smoothed the reticence to try a fresh approach. Jitti, who founded Bangkok’s Unfolding Kafka Festivals, built on the fusion of old and new in his 12 Monkeys Dance Theatre, to combine National Theatre players with his idiosyncratic choreography and staging.

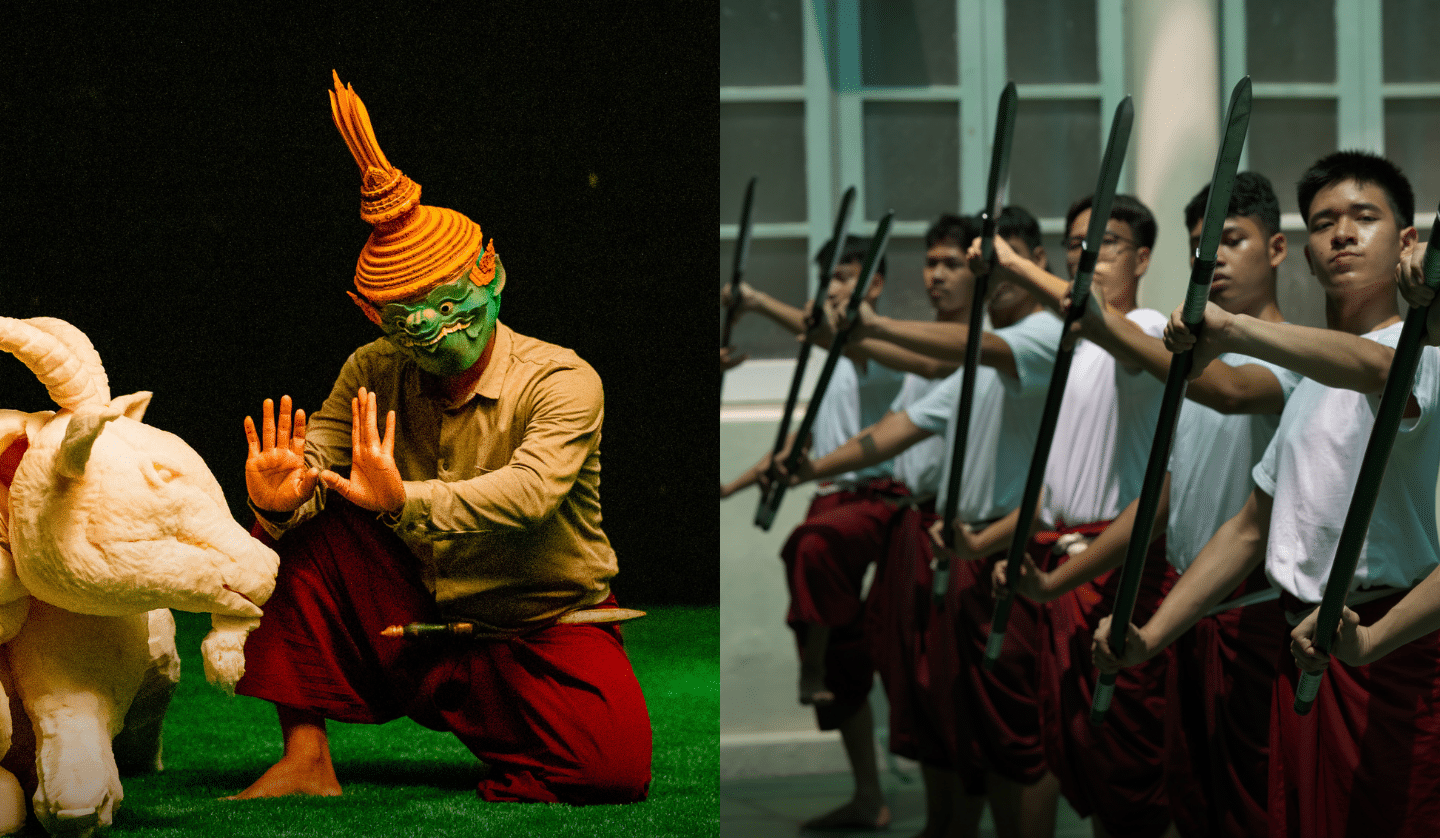

Their 55-minute documentary, ‘Miscellany of Khon’, demystifies some of its secrets. Instead of dumbing down, the film sparks curiosity by revealing six details, each explained by an insider and shown through an abstract dance. Jitti uses neutral costumes and backdrops, to highlight each detail. Unnervingly, dancers wear a plain white mask backwards, so we gaze at the face while seeing the arm and leg gestures from behind. It really grabs your attention.

The film takes us backstage and humanises the performers, literally going behind their mask. Anyone who’s put on a Khon mask soon finds that it doesn’t move in sync as you turn! The trick is that dancers bite on a string attached inside, giving them the control and confidence to enable its fixed features to convey emotion through slight tilts of the head. Similar thread is used to stitch the costume onto the body each time, making the dancer and character as one.

Masks limit the dancers’ vision, so they coordinate using sound. The narrator’s mannered singing indicates postures and gestures. And Khon’s military origins emerge through baak, a two-way signalling technique that we hardly notice amid the melody. Stick and drum percussion prompts dancers’ movements, which can in turn cue the musicians.

We also learn about Ramayana tales that aren’t performed in Khon, and how the characters’ transformations can be conveyed through the chui-chai singing style derived from eerie pleng rua (boat songs). Depth of character can emerge through subtleties like dangling a garland on the mask of the demon king Thotsakan, revealing his fatal vulnerability: love for the heroine Nang Sida.

Khon’s female roles were originally played by men. After decades of casting women, whenever men play heroines today their gestures can seem exaggerated, so one such dancer advocates for that lost skill to be revived. Yet the dancer of Queen Montho in Jitti’s show displays such mature femininity you’d never know.

Fresh perspectives can also come from changing the props and set. Scenes in the film are set in corridors, hotels and the beach. The dances feature modern objects, like toys, mechanical animals and a bath. On August 16 and 17, they will stage ‘The Golden Deer Incident’ and ‘Melancholy of Mandodari’ in Khao Yai Art Forest, under Maman, a gigntic bronze statue of a mother spider sculpted by the late Louise Bourgeois for London’s Tate Modern.

Khon becomes more compelling once you grasp what’s going on. Across the world, secret knowledge preserves the status of initiates in their ivory tower, but modern people can tire of traditions that they are told to love. Yes, breaking those codes does lessen mystique, but it adds appreciation of the skill and culture that makes Khon not just heritage but creative entertainment.

Jitti conceded how hard it was to blend his contemporary choreography with masters of the classical tradition, but that not involving the National Theatre would have been problematic in other ways. Pichet Klunchun’s pursuit of independent Khon has overcome tough barriers and official scolding. He was trained by a fellow outsider, as enacted in his pointedly titled show ‘I am a Demon.’ His performance lecture with choreographer Jerome Bel, ‘My Name is Pichet Klunchun,’ broke the taboo of dancers remaining anonymous artisans. Now Miscellany of Khon also recognises several talents behind Khon. In today’s individualist online world, Khon can’t avoid the need to relate narratives about the people who create it.

Pichet Klunchun Dance Company has since flourished through independent shows, international festivals and his own theatre. His mission has deconstructed the essence of Khon’s energetic movement and practice routines, mostly plain clothed. He then explores Khon’s possibilities, from its spiritual and martial roots into futuristic digital realms. His remarkable discoveries culminate in the recently premiered ‘Number 60,’ which goes beyond Khon’s manual of 59 set poses to let the dancer freely evolve.

Foreign audiences have typically been receptive earlier than Thailand. Many works by Jitti and Pichet, including these ones, were premiered abroad. Both have received the French cultural knighthood, the Chevalier des arts des lettres, while Pichet eventually earned the Thai Silpathorn Award and heads the Performing Arts Committee in the state’s creative culture organisation, THACCA.

Jitti’s initiative to create a National Centre for Choreography gives Thai dance a much needed foundation to nurture talent, develop professional standards, conduct research and exchange knowledge, without bureaucracy, certification constraints or rigid mindsets. It would bring in mentorship by the likes of Pichet and masters of neglected regional dances, with the first project started in Isaan at Khon Kaen. It would not just bring innovation, but also tap the unrealised potential within traditions.

Reassuringly, one effect of innovation is to rekindle interest in the authentic original. As opera, ballet and kabuki prove, old and new forms can coexist. Still, it needs serious support and resources to cultivate a new generation of choreographers – and help Khon fulfil Nai Butr’s early soft power potential from a century ago.

National Theatre dancers will perform Jitti’s dances at ‘Farewell to Maman’, Khao Yai Art Forest, Pak Chong, 16-17 August, 10am-7pm. Event includes Live Mandala, Fog Forest, print-making workshops, art installations, forest trails and Khon performances of ‘The Golden Deer Incident’ at 3.30pm & ‘Melancholy of Mandodari’ at 5.30pm.

Tickets 1,500 THB or 4,500 THB including champagne dinner 7-9pm & Sunday afterparty till 10pm.

Tickets from ticketmelon.com/kyaf/farewelltomaman.

Contact Khao Yai Art Forest via Facebook or 085-501 4886.

This twice-monthly column, Very Thai, is syndicated by River Books, publisher of Philip Cornwel-Smith’s bestselling books Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture and Very Bangkok: In the City of the Senses.

The views expressed by the author of this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Koktail magazine.

Photos by Philip Cornwel-Smith, unless credited with kind permission to Jitti Chompee or Phichet Klunchun Dance Company

Join Urassaya “Yaya” Sperbund in her kitchen where family, culture, and Norwegian ...

Saturdays are already made for Salmon, now there's even more reason to ...

What’s your #MySalmonStory? Join Thailand’s Tastiest Movement with Seafood from Norway There’s ...

VERY THAI: In this regular column, author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture and topics ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Twisted punishments and psychological horror return in Girl from Nowhere: The Reset, starring ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy