Black Grills: Homage to the Asian Tradition of Blackened Teeth, Once a Mark of High Status

Courtesy of @sailorr Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger ...

Som Det Theatre, Som Det district, Kalasin, Thailand (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Jablon)

[This article was first published in January 2020.]

One of the most impressive things about Bangkok, aside from the food and the temples and the shopping outlets, is the abundance and accessibility of world-class movie theatres. Almost every mall in the city—that’s a lot of malls—has a modern multiplex showing the latest Hollywood blockbusters, and without breaking the bank by any means, you can easily upgrade to premium seats that might even come with blankets.

But while the price of this luxury may seem laughably inexpensive, it comes at a cost of history that’s not being covered by anyone really. You see, not too long ago, there weren’t just two main players in the cinema business like there is today in Bangkok and other major cities in Thailand. Rather, there were hundreds of independent cinema operators throughout the nation, each curating their own architectural style and picks of flicks.

Enchanted by and nostalgic for this golden age of cinema, one man, Philip Jablon, is hunting down the last remaining standalone theatres in the region, in an effort to document them and ultimately make a case for their preservation in a rapidly transforming world. We met this Philly native on his recent stop by Bangkok for coffee and a chat about cinema and his mission to save independent movie theatres across Southeast Asia.

Your project—the Southeast Asia Movie Theatre Project—begins in Thailand. What brought you here in the first place?

I came here to study sustainable development at Chiang Mai University, with the intention of eventually working for an international development agency, like the UN or something smaller. Save the people of the world—that was my thought at the time.

And now you’re trying to save theatres of the world.

Exactly.

So tell us about the project. What is the idea and what are you trying to achieve ultimately?

The idea is basically to document these buildings, standalone-style movie theatres, while they still exist and to bring them into the public eye and to the attention of local people more than anything else. I know that in the region economies are moving very rapidly and people are often looking straight forward, erasing history very quickly without much thought to it. So my idea was that if people see these theatres and become interested in them, then maybe there’ll be some sort of a movement to preserve some of them.

What made you commit to theatres, of all topics?

Well, movie theatres are something different. I grew up in Philly, close to downtown, and we went to movie theatres all the time when I was a little kid. There were standalone movie theatres up and down the central part of Philadelphia. It was just a part of my life. I didn’t think much about it. By the time I became an adult though, all those theatres were gone. If you want to go to the movies now, you have to go to the megaplex on the edge of the city. I thought ‘this sucks’ and also no one’s putting any thought into preserving standalone theatres. Meanwhile, my interest started changing. I came to live in Southeast Asia and one day, while I was trying to get my bearings in school and figure out what I wanted to do, I accidentally stumbled across an old movie theatre.

Tell us the story.

In Chiang Mai, there was the public Tippanetr theatre. Prior to discovering this theatre, I had only known of theatres in shopping malls. So when I found this, something like what we used to have in Philadelphia with a similar kind of local entertainment history that’s not attached to a shopping mall, I was in awe. I talked to my friends and we decided that we were going to see a movie there. But we delayed and delayed, and by the time we got around to it, it was gone. It had been demolished. I was so disappointed, but it was that act of destruction that made me want to look more at movie theatres, to find more.

Siri Phanom Rama, Phanom Sarakam, Chachoengsao, Thailand (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Jablon)

Since starting in 2008, how many theatres have you documented? Do you have a number?

It’s around 300. Most of them are in Thailand, followed by Myanmar and then Laos.

About how many in Thailand?

Over 100 I’d say. Almost every tambon used to have its own movie theatre. Definitely almost every amphur. Every amphur used to have one or two, maybe three big ones. Even the sub-districts often had their own little movie theatre, made of wood. I haven’t gone to every district and every sub-district, but I think I’ve been to 72 out of the 76 provinces in Thailand.

Scala theatre (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Jablon)

Do you have a favourite theatre so far?

It’s the Scala. Scala is just a great theatre. It’s a very unique theatre architecturally. It’s comfortable. It’s beautiful. It’s right in the middle of one of the biggest cities in the region, and it has a life of its own. The Scala is its own physical entity, and it embodies what interests me about these old movie theatres, which is location, architecture and social function.

As you know, Lido has been recently renovated, and they’ve kept one of the three original screening rooms functional. How do you feel about that?

I just went there yesterday and I actually liked it. I was impressed. I feel like it was kind of simple what they did. They basically took all the old wall coverings off, stripped it down and made it look very chic. I feel like they’ve reinvented it. I had heard mixed reviews from other people before I went to see it for myself. I haven’t been in the theatre spaces yet, but what I saw was impressive. At the lower level, there are all these little shops, cat cafes and even a radio station where you can see the DJ interviewing guests. Then upstairs, you’ve got a movie theatre and event space. I thought it was really cool actually. It felt like exactly what these spaces can and should be, which is a gathering space where culture’s happening in one form or another.

What movie do you have a fond memory of watching in the theatres?

One of the most exciting experiences I’ve had in the theatre was actually about 10 years ago in Chiang Mai. The movie was called Haa Prang. It’s an omnibus of short movies, horror movies in one comedy. I saw it at Vista Kad Suan Kaew, one of the local theatre chains in Central Kad Suan Kaew shopping mall. They had huge viewing auditoriums—there must have been like 600 seats in each of these auditoriums. I went to this movie with my girlfriend, and it was packed with all young kids from Chiang Mai. It was just so much fun. People were shrieking and jumping. The crowd was just so into it, and you really feel like you’re part of a collective experience, having a good time with all these people.

“The Scala is its own physical entity, and it embodies what interests me about these old movie theatres, which is location, architecture and social function.”

When you go around documenting standalone movie theatres, you also find their backstories. What is the process? How do you go about piecing together their stories?

Totally by talking to people. That’s how I get 95 per cent of my information. Sometimes it’s wrong. Sometimes I get different stories. You just kind of have to distil it down and figure out what might be the truth. Basically, I get off a bus or a train, walk into town and try to identify people who look like they’ve been in the town for a long time. Generally, people who are older than me, senior people, shopkeepers, who might actually really know the lay of the land. Then I start asking, and that would lead me on the path and I go track it down and go from there.

I noticed in your book that, besides photographs of the theatres themselves, there are also photographs of ticket stubs and other artefacts related to the theatres. How do you go around collecting those?

When I first started this project, there were actually a lot of active standalone movie theatres in Thailand, and anytime I have encountered one, I’d buy a ticket, just to give a little support to the theatre. I started collecting them, but there are no more active standalones out there. So I’ve been looking to collectors and trying to track down old people to see if maybe they have an old ticket hanging around their house that they never threw away.

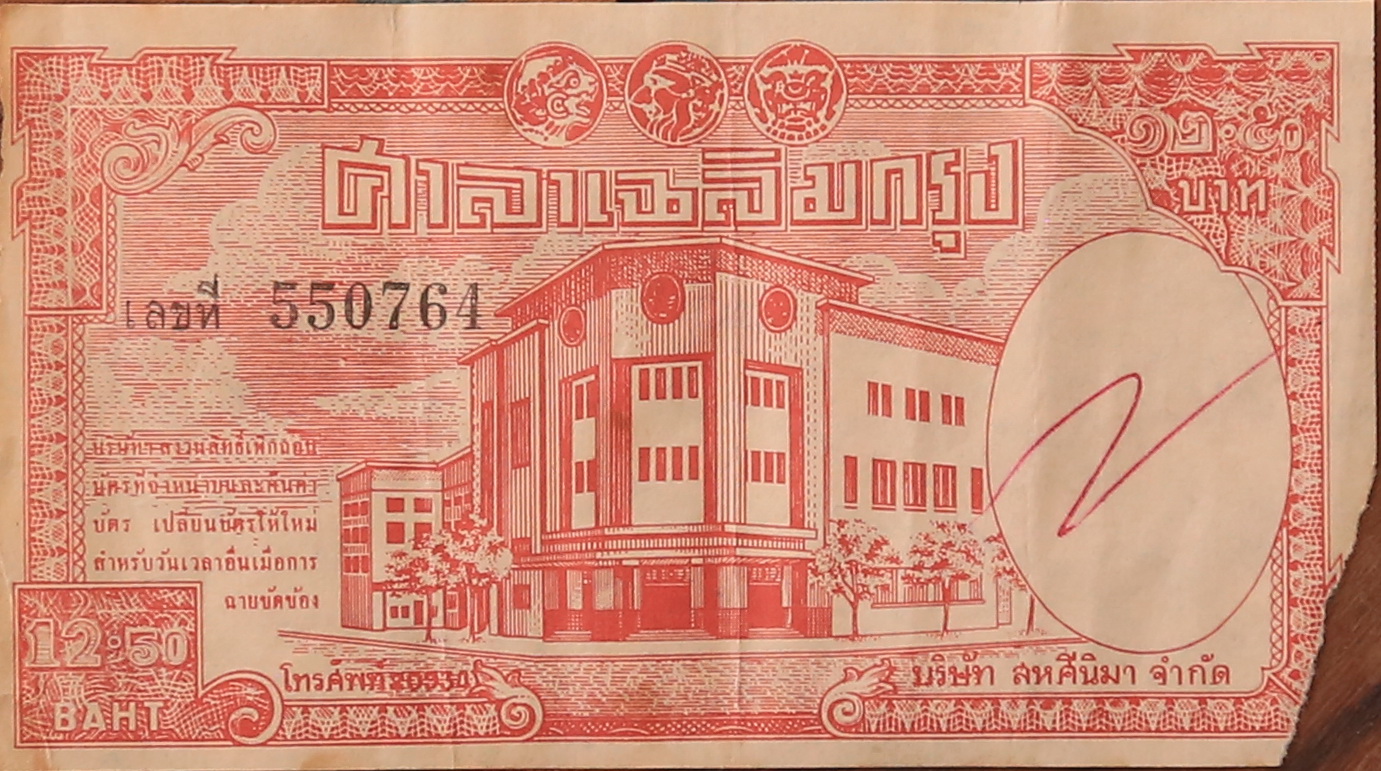

Sala Chalerm Krung ticket (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Jablon)

Besides the race against time, what are some challenges you’ve faced throughout the entire process, from start until now?

So many. First, the language barrier. When I first started, my Thai was pretty weak. I think it’s improved over the years from this work, from going to places where there aren’t any English-speaking people. That was a challenge that I turned into an attribute. Another challenge is unhelpful or unsympathetic theatre owners?

How so?

Say I’ve travelled a long way to get to a particular theatre because I heard it exists. I finally reach it and I make contact with the owner, and they’re just completely dismissive and want nothing to do with me and won’t let me photograph their building. That’s very frustrating. Some people are just so protective of their assets. I had one incident where I was invited by a local architect from this town to come and look at a movie theatre. The architect was hired by the owner of the theatre to basically reinvent it as it had been abandoned for a long time. So I went to see it and got the full tour. There were two owners, who were sisters. One of them was so sweet, telling me her whole family history and how this theatre came to be and how she wanted to spread the word about it. I wrote an article about the theatre and after it was published, the other sister sent me a nasty email and mildly threatened me. It was unfortunate, but that’s the kind of challenges you face sometimes.

Burapha Theatre auditorium (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Jablon)

You’re obviously still travelling and searching for theatres. Is there going to be a second book?

I’d like to make another book—the Movie Theatres of Myanmar. I haven’t started it yet, but I’ve got enough material to fill a book.

Will you be doing this for a really long time?

Yeah, I think so. For as long as I can.

Do you think there is ultimately hope for independent theatres the way the world’s going?

There’s always hope. You have to have the right combination of motivated people who have the resources and an audience. I think in a place like Bangkok where there’s a lot of educated people and it’s a very international place, there’s definitely space for alternate kinds of cinema. And it’s being proven. You have the Frieze Green Club, Bangkok Screening Room, Lido, Scala, the Thai Film Archive—they put on this classic film series at the Scala and every time I go, it’s always a mob, hundreds and hundreds of people. So there’s definitely a market for this. I’d like to see it keep growing and have more alternatives to the big multiplexes.

Fa Siam, Suphanburi (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Jablon)

Keep up with Philip’s work at fb.com/SEAMTP.

Courtesy of @sailorr Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger ...

Pets, as cherished members of our families, deserve rights and protections that ...

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Must-have gadgets for kids in the Y2K are, predictably, making a comeback ...

The feral lime-green feminine frequency that won't stop multiplying Somewhere last year ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy